Theodora (wife of Justinian I)

| Theodora | |

|---|---|

| Byzantine Empress | |

|

|

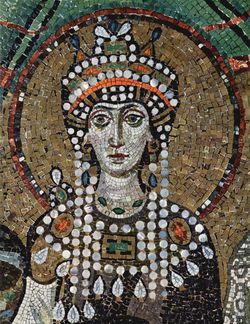

| Theodora, detail of a Byzantine mosaic in Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna | |

|

|

|

| Tenure | 9 August 527 - 28 June 548 (20 years, 324 days) |

| Predecessor | Euphemia |

| Successor | Sophia |

| Spouse | Justinian I |

| Issue | |

| John, Theodora (both illegitimate) | |

| Full name | |

| Theodora | |

| Father | Acacius |

| Mother | Theodora? |

| Born | c. 500 Famagusta, Cyprus |

| Died | 28 June 548 (aged 48) Constantinople |

| Burial | Church of the Holy Apostles |

Theodora (Greek: Θεοδώρα) (c. 500 - 28 June 548), was empress of the Byzantine Empire and the wife of Emperor Justinian I. Like her husband, she is a saint in the Orthodox Church, commemorated on the 14th of November.[1] Theodora was perhaps the most influential and powerful woman in the Byzantine Empire's history.

Contents |

Historiography

The main historical sources for her life are the works of Procopius. However the historian has offered three contradictory portrayals of the Empress. The Wars of Justinian, largely completed in 545, paints a picture of a courageous and influential empress. Sometime after their publication, he wrote the Secret History. The Secret History reveals an author who had become deeply disillusioned with the emperor Justinian and his wife, as well as with General Belisarius, his former commander and patron, and Belisarius' wife Antonina, even to the point of attributing the general's exceptional and historic accomplishments to a weak and ridiculous man.

The anecdotes claim to expose the secret springs of their public actions, as well as the private lives of the Emperor, his wife, and their entourage. Justinian is depicted as cruel, venal, prodigal and incompetent; as for Theodora, the reader is treated to a detailed and titillating portrayal of vulgarity and insatiable lust, combined with shrewish and calculating mean-spiritedness; yet much of the work covers the same time period as The Wars of Justinian. This work was not published at the time.

The Buildings of Justinian, written about the same time as the Secret History, is a panegyric which paints Justinian and Theodora as a pious couple and presents particularly flattering portrayals of them. Besides her piety, her beauty is excessively praised. Although Theodora was dead when this work was published, Justinian was very much alive, and probably commissioned the work.[2]

Various other historians presented additional information on her life. Theophanes the Confessor mentions some familial relations of Theodora to figures not mentioned by Procopius. Victor Tonnennensis notes her familial relation to the next empress, Sophia. Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos traces her origin to Cyprus. Patria, attributed to George Codinus, claims Theodora came from Paphlagonia. Michael the Syrian, the Chronicle of 1234 and Bar-Hebraeus place her origin in the city of Daman, near Kallinikos, Syria. They contradict Procopius by making Theodora the daughter of a priest, trained in the pious practices of Monophysitism since birth. John of Ephesus mentions an illegitimate daughter not named by Procopius.[3]

Early years

Origin

Theodora, of Greek Cypriot descent,[4] was born according to some historians on the island of Crete in Greece, but others list her birthplace as Syria. Nicephorus Callistus Xanthopoulos names Theodora a native of Cyprus. Patria, attributed to George Codinus, claims Theodora came from Paphlagonia. The Patria claims she was later employed in Constantinople, spinning wool. Michael the Syrian, the Chronicle of 1234 and Bar-Hebraeus place her origin in the city of Daman, near Kallinikos, Syria. They contradict Procopius by making Theodora the daughter of a bear trainer, trained in the pious practices of Miaphysitism since birth. She was introduced to Justinian during one of his visits to the eastern provinces and later married. These are Miaphysite sources and record her depiction among members of their creed. The Miaphysites have tended to regard Theodora as one of their own and the tradition may have been invented as a way to improve her reputation. These accounts are usually ignored in favor of Procopius.[3] While Evans considers tales of entertaining notables at banquets and accepting multitudes of lovers to be mostly factual, the image of Theodora's "voracious" appetite for sexual intercourse may have more to do with rumors and lewd jokes than the actual extent of her activities.[2]

In "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204" (1999) by Lynda Garland it is noted that John of Ephesus reports Theodora coming from a brothel. Unlike Procopius, John happened to be a favourite of the Empress and his historical portrayal of his patron is mostly positive. Garland points that while it confirms Procopius' account of Theodora as a prostitute, there seems to be little reason to believe she worked out of a brothel "managed by a pimp". Employment as an actress at the time would include both "indecent exhibitions on stage" and providing sexual services off stage. In what Garland calls the "sleazy entertainment business in the capital", Theodora would earn her living by a combination of her theatrical and sexual skills. Garland considers it important that John was familiar with Theodora's background. He was not a resident of Constantinople and his autobiographical accounts do not include even visiting the capital until Theodora was well into her career as an Empress. This would imply that Theodora's background as an actress and courtesan was general knowledge at the time of Justinian's reign.[5]

Travels

Theodora later followed Hecebolus, a Tyrian who had been made governor of Pentapolis, apparently as his mistress. Leaving him, she came next to Alexandria and eventually worked her way to Constantinople.[6] Evans points that her motivation in following Hecebolus could be in seeking a way to escape her profession. A law established in 409 under the reign of Theodosius II, "barred local authorities from transferring actors from their cities", in effect also limiting the ability of actors to travel to other cities. Theodora "might have encountered legal obstacles to her desertion of the stage" and relied on the protection of Hecebolus to manage overcoming them. She is said by later sources to have met the Patriarch Timothy III in Alexandria, who was Monophysite, and it was at that time that she converted to Monophysite Christianity.[2]

Traveling through Antioch during this period, Theodora found a pivotal ally, a dancer named Macedonia.[6] Evans notes that Justinian had succeeded Vitalian as magister militum in praesenti and that Macedonia seems to have served as one of his informants. She is the first known link between Theodora and Justinian. There are theories that the informant was the one who introduced the later imperial couple to each other. However, Procopius is silent on the subject and the connection remains a conjecture.[2]

Mistress and wife of Justinian

"Thus was this woman born and bred, and her name was a byword beyond that of other common wretches on the tongues of all men. But when she came back to Constantinople, Justinian fell violently in love with her. At first, he kept her only as a mistress, though he raised her to patrician rank. Through him Theodora was immediately able to acquire an unholy power and exceedingly great riches. She seemed to him the sweetest thing in the world, and, like all lovers, he desired to please his charmer with every possible favor and requite her with all his wealth. The extravagance added fuel to the flames of passion. With her now to help spend his money he plundered the people more than ever, not only in the capital, but throughout the Roman Empire. As both of them had for a long time been of the Blue Party, they gave this faction almost complete control of the affairs of state. It was long afterward that the worst of this evil was checked.[7]

"Now as long as the former Empress was alive, Justinian had to find a way to make Theodora his wedded wife. In this one matter she opposed him as in nothing else: for the lady abhorred vice, being a rustic and of barbarian descent, as I have shown. She was never able to do any real good, because of her continued ignorance of the affairs of state. She dropped her original name, for fear people would think it ridiculous, and adopted the name of Euphemia when she came to the palace. But finally her death removed this obstacle to Justinian's desire. Justin, doting and utterly senile, was now the laughing stock of his subjects; he was disregarded by everyone because of his inability to oversee state affairs. But for Justinian, they all served with considerable awe. His everything was in his hand, and his passion for turmoil created universal consternation."[8]

"It was then that he undertook to complete his marriage with Theodora. But as it was impossible for a man of senatorial rank to make a courtesan his wife, this being forbidden by ancient law, he made the Emperor nullify this ordinance by creating a new one, permitting him to wed Theodora, and consequently making it possible for anyone else to marry a courtesan. Immediately after this he seized the power of the Emperor, veiling his usurpation with a transparent pretext: for he was proclaimed colleague of his uncle as Emperor of the Romans by the questionable legality of an election inspired by terror. So Justinian and Theodora ascended the imperial throne three days before Easter, a time, indeed, when even making visits or greeting one's friends is forbidden. And not many days later Justin died of an illness, after a reign of nine years. Justinian was now sole monarch, together, of course, with Theodora."[8] Evans notes that the new law can be found in Corpus Juris Civilis.[2]

In fact it is included in Book 5, title 4, chapter 23. "Deeming it the proper subject of imperial benevolence to investigate and at all times foster the advantages of our subjects, we think that the errors also of women, through which, on account of the frailty of their sex, they may choose a mode of life unworthy of their honor, should be corrected by proper restraint, so that they may not be deprived of the hope of a better condition, but may look forward to that and thus more easily avoid an inconsiderate and dishonorable alliance. For we believe that we can thus imitate, as much as it possible for us to do, the benevolence and great clemency of God to the human race, who contescends always to pardon the daily sins of men, to receive our rependance and to lend us back to a better condition: if we fail to do this in the case of those subjected to our sway, we shall be unworthy of forgiveness."[9]

- "Thus since it would be unjust that slaves should be able to receive their freedom by imperial indulgence and be restored to their natural rights so as to live, upon bestowal of imperial beneficence of that kind, as if they had never been slaves and had always been free born, but that women, who have been on the stage, but who have changed their mind and have abandoned a dishonorable profession, should have no hope of imperial beneficence which might lead them back to the condition in which they might have lived if they had not sinned, we grant them by this beneficent imperial sanction the right that, if they abandon their dishonorable conduct, and embrace a better and honorable mode of life, they may supplicate our majesty, and they will unhesitatingly be granted asn imperial rescript permitting to enter into a legal marriage."[9]

- "Persons who marry them need not fear that such alliance will be invalid under the provisions of our former laws, but may be confident that such matrimony shall be as valid as if their wives had not previously lived any dishonorable life, whether the husbands possess a title or are otherwise forbidden to marry women that have been on the stage, provided that such alliance must be proven by marriage documents, and not otherwise."[9]

- "Such women shall be entirely cleansed of all stain as if they had been returned to their natal condition. No dishonor shall adhere to them, and we want no difference to exist between them and those who have not sinned in a similar matter".[9]

The same law also includes regulations making children produced by said marriages legitimate, gives the former actresses rights to inherit estates and transfer property to others prior to their marriage and allows women who hold titles to marry beneath their station. The daughters of actresses also had legal limitations. The future daughters of former actresses benefiting from this law had no such limitations. Already living daughters of former actresses could petition the emperor to remove such legal restrictions from them. The law extended the right to petition also to daughters of active actresses. The law also retroactively acknowledged already existing marital alliances between partners of unequal status, legitimizing their status. Justin makes a point however that the marital alliances permitted by the law should not be "nefarious" or "incestuous"[9]

"Thus it was that Theodora, though born and brought up as I have related, rose to royal dignity over all obstacles. For no thought of shame came to Justinian in marrying her, though he might have taken his pick of the noblest born, most highly educated, most modest, carefully nurtured, virtuous and beautiful virgins of all the ladies in the whole Roman Empire: a maiden, as they say, with upstanding breasts. Instead, he preferred to make his own what had been common to all men, alike, careless of all her revealed history, took in wedlock a woman who was not only guilty of every other contamination but boasted of her many abortions." ... "However, not a single member of even the Senate, seeing this disgrace befalling the State, dared to complain or forbid the event; but all of them bowed down before her as if she were a goddess. Nor was there a priest who showed any resentment, but all hastened to greet her as Highness. And the populace who had seen her before on the stage, directly raised its hands to proclaim itself her slave in fact and in name. Nor did any soldier grumble at being ordered to risk the perils of war for the benefit of Theodora, nor was there any man on earth who ventured to oppose her. Confronted with this disgrace, they all yielded, I suppose, to necessity, for it was as if Fate were giving proof of its power to control mortal affairs as malignantly as it pleases, showing that its decrees need not always be according to reason or human propriety. Thus does Destiny sometimes raise mortals suddenly to lofty heights in defiance of reason, in challenge to all out cries of injustice; but admits no obstacle, urging on his favorites to the appointed goal without let or hindrance. But as this is the will of God, so let it befall and be written."[8]

Description

"Now Theodora was fair of face and of a very graceful, though small, person; her complexion was moderately colorful, if somewhat pale; and her eyes were dazzling and vivacious. All eternity would not be long enough to allow one to tell her escapades while she was on the stage, but the few details I have mentioned above should be sufficient to demonstrate the woman's character to future generations."[8]

Ascent to the Byzantine throne

Justinian was crowned augustus (emperor) and Theodora augusta on 4 April 527, giving them control of the Byzantine Empire. A contemporary official, Joannes Laurentius Lydus, remarked that she was "superior in intelligence to any man".[10] Justinian clearly recognized this as well, allowing her to share his throne and take active part in decision making. As Justinian writes, he consulted Theodora when he promulgated a constitution that included reforms meant to end corruption by public officials.[11]

The imperial status of Theodora also proved profitable for her relatives. Her sister Comito became the wife of a rising young officer, Sittas, though he was to die young while campaigning in Armenia. Her niece Sophia married the nephew of Justinian, Justin II, who succeeded his uncle in 565.

Partnership in power

According to Procopius: "What she and her husband did together must now be briefly described: for neither did anything without the consent of the other. For some time it was generally supposed they were totally different in mind and action; but later it was revealed that their apparent disagreement had been arranged so that their subjects might not unanimously revolt against them, but instead be divided in opinion."

"Thus they split the Christians into two parties, each pretending to take the part of one side, thus confusing both, as I shall soon show; and then they ruined both political factions. Theodora feigned to support the Blues with all her power, encouraging them to take the offensive against the opposing party and perform the most outrageous deeds of violence; while Justinian, affecting to be vexed and secretly jealous of her, also pretended he could not openly oppose her orders. And thus they gave the impression often that they were acting in opposition. Then he would rule that the Blues must be punished for their crimes, and she would angrily complain that against her will she was defeated by her husband. However, the Blue partisans, as I have said, seemed cautious, for they did not violate their neighbors as much as they might have done."[8]

"And in legal disputes each of the two would pretend to favor one of the litigants, and compel the man with the worse case to win: and so they robbed both disputants of most of the property at issue. In the same way, the Emperor, taking many persons into his intimacy, gave them offices by power of which they could defraud the State to the limits of their ambition. And as soon as they had collected enough plunder, they would fall out of favor with Theodora, and straightway be ruined. At first he would affect great sympathy in their behalf, but soon he would somehow lose his confidence in them, and an air of doubt would darken his zeal in their behalf. Then Theodora would use them shamefully, while he, unconscious as it were of what was being done to them, confiscated their properties and boldly enjoyed their wealth. By such well-planned hypocrisies they confused the public and, pretending to be at variance with each other, were able to establish a firm and mutual tyranny."[8]

Courtly life

Events of the reign

John Malalas lists the building projects of Justinian during the first year of his reign (527-528). He then lists the projects of the "most devout" Theodora for the same period. The first mentioned by name was a church dedicated to Michael the Archangel and built in Antioch. Next mentioned is the Basilica of Anatolius, also located in Antioch. He places special attention to the columns of the Basilica being send there from Constantinople. He also mentions Theodora sending a cross decorated with pearls to Jerusalem.[12]

According to John Malalas, Eulalios, a Comes domesticorum with financial difficulties, died and left the care of his three daughters to Justinian in 528. Malalas notes that he did not leave an estate sufficient for their care, nor sufficient amounts for the dowries and properties intended in his will. Justinian assigned Makedonios as curator of their inheritance. He was charged with repaying any debts left to the orphan girls. The three were placed in the custody of Theodora and "looked after in the imperial apartments". By imperial decision the dowries and properties originally intended for them would be provided by funds of the imperial couple. Garland considers it a case of Theodora taking interest in women's issues.[13]

In 529, Malalas records a visit of Theodora to Pythion (Yalova), in particular its hot springs. She was accompanied by patricians, cubicularii (chamberlains), the comes sacrarum largitionum (Master of the 'Sacred Largess', who operated the imperial finances) and an overall retinue of no less than four thousand people. He lists her generous donations to churches she visited in her short journey. Theophanes the Confessor gives a listing of the high-ranking courtiers accompanying her. He makes a dating mistake, placing the visit in 532. Garland considers the imperial splendor of an otherwise uneventful trip to a spa an indication of Theodora having adapted to heading "an intricate and formal court".[14]

Theodora proved herself a worthy and able leader during the Nika riots. There were two rival political factions in the Empire, the Blues and the Greens, which started a riot stemming from many grievances in January 532, during a chariot race in the hippodrome. The rioters set many public buildings on fire and proclaimed a new emperor. Theodora proved herself ruthless, as it was her will that Pompeius and Hypatius, the nephews of Anastasius I, be put to death when the mob had chosen Hypatius to replace Justinian. Unable to control the mob, Justinian and his officials prepared to flee. At a meeting of the government council, Theodora spoke out against leaving the palace and underlined the significance of someone who died as a ruler instead of living as nothing. Her determined speech convinced them all. As a result, Justinian ordered his loyal troops led by two reliable officers, Belisarius and Mundus, to attack the demonstrators in the hippodrome. His generals attacked the hippodrome, killing over 30,000 rebels. Historians agree that it was Theodora's courage and decisiveness that saved Justinian's reign.

Following the Nika revolt, Justinian and Theodora executed their surviving political rivals and reformed Constantinople making it the most splendid city the world had seen for centuries, building or rebuilding aqueducts, bridges and more than twenty five churches. The greatest of these is Hagia Sophia, considered the epitome of Byzantine architecture and one of the architectural wonders of the world.

The "Buildings of Justinian" by Procopius mentions Theodora involved in several other projects. He starts by mentioning a hospice located between Hagia Sophia and Hagia Irene. "Between these two churches there was a certain hospice, devoted to those who were at once destitute and suffering from serious illness, those who were, namely, suffering in loss of both property and health. This was erected in early times by a certain pious man, Samson by name. And neither did this remain untouched by the rioters [in the Nika riots], but it caught fire together with the churches on either side of it and was destroyed. The Emperor Justinian rebuilt it, making it a nobler building in the beauty of its structure, and much larger in the number of its rooms. He has also endowed it with a generous annual income of money, to the end that through all time the ills of more sufferers may be cured. But by no means feeling either a surfeit or any sort of weariness in shewing honour to God, he established two other hospices opposite to this one in the buildings called respectively the House of Isidorus and the House of Arcadius, the Empress Theodora labouring with him in this most holy undertaking."[15] He also mentions Theodora involved in the building of a xenodocheion.[12] When mentioning the building projects of Justinian in Bithynia, Procopius mentions Theodora involved in the road which had fallen into disrepair. "There is a certain road in Bithynia leading from there into the Phrygian territory, on which it frequently happened that countless men and beasts too perished in the winter season. The soil of this region is exceedingly deep; and not only after unusual deluges of rain or the final melting of very heavy snows, but even after occasional showers it turns into a deep and impassable marsh, making the roads quagmires, with the result that travellers on that road were frequently drowned. But he himself and the Empress Theodora, by their wise generosity, removed this danger for wayfarers. They laid a covering of very large stones over this highway for a distance of one half a day's journey for an unencumbered traveller and so brought it about that travellers on that road could get through on the hard pavement."[16] She also took interest in projects located in North Africa. "First, then, he cared for Carthage, which now, very properly, is called Justinianê, rebuilding the whole circuit-wall, which had fallen down, and digging around it a moat which it had not had before. ... He built stoas on either side of what is called the Maritime Forum, and a public bath, a fine sight, which they have named Theodorianae, after the Empress." ... "In the surrounding region, which is called Proconsularis, there was an unwalled city, Vaga by name, which could be captured not only by a planned attack of the barbarians, but even if they merely chanced to be passing that way. This place the Emperor Justinian surrounded with very strong defences and made it worthy to be called a city, and capable of affording safe protection to its inhabitants. And they, having received this favour, now call the city Theodorias in honour of the Empress."[17]

Theodora also created her own centers of power. The eunuch Narses, who in old age developed into a brilliant general, was her protege, and so was the praetorian prefect Peter Barsymes. John the Cappadocian, Justinian's chief tax collector, was identified as her enemy, because of his independent influence.

Legislation

Theodora participated in Justinian's legal and spiritual reforms, and her involvement in the increase of the rights of women was substantial. Garland points several laws of Justinian who seem surprisingly favorable to women. Until 528, laws about rape only concerned women above the rank of barmaids, effectively making the rape of lower-class women and slaves legal. In 528, a law on sexual offenses changed the status considerably. Rapists and kidnappers of women, both free-women and female slaves, were given the capital punishment. The law also included sections against the unlawful seduction of women. A 534 law made it illegal to force any woman on the theatrical stage without their consent, regardless if said woman was free or a slave. In 535, laws against procurers address the specific problem of those who force underage girls into prostitution. The law mentions the practice of procurers first luring young girls at the age of ten or younger away from their parents with promises of food and clothing and secondly forcing said girls "into a life of unchastity". This was rendered illegal by this law and promises or agreements between the girls and their pimps were clarified as illegal as well. The same year, another law dictates that marriages are created by "mutual affection", not agreements on the dowry. The repudiation of women who married without dowry was therefore rendered illegal. A 537 law allowed actresses to renounce their occupation at will. Attempts to force them to continue the employment by invoking oaths or previous agreements were rendered illegal and punishable by fines. Garland notes that Theodora, having first-hand experience with the hardships faced by the women of the lower classes, was likely to be the motivating force behind laws attempting to improve their living conditions. However, Justinian seems to have continued reforms in that direction even following her death. For example, a 559 law put an end to the practice of women being imprisoned on charges of debt. They were to remain free and attempt to repay their debts. The same law changed the status of women held prisoners for more serious offenses. They were to be placed in monasteries in the care of nuns or placed under guard of other "reliable" women. The law specifies that the law was an attempt to prevent the rape and ill-treatment of female prisoners.[18] Theodora had laws passed that closed brothels. She also expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership, instituted the death penalty for rape, forbade exposure of unwanted infants, gave mothers some guardianship rights over their children, and forbade the killing of a wife who committed adultery.

Evagrius Scholasticus considers the severity of treatment for men accused of rape to have been excessive and adds it to his mostly negative portrayal of Justinian.[19] By his account: "Justinian was insatiable in the acquisition of wealth, and so excessively covetous of the property of others, that he sold for money the whole body of his subjects to those who were entrusted with offices or who were collectors of tributes, and to whatever persons were disposed to entrap others by groundless charges. He stripped of their entire property innumerable wealthy persons, under colour of the emptiest pretexts. If even a prostitute, marking out an individual as a victim, raised a charge of criminal intercourse [rape] against him, all law was at once rendered vain, and by making Justinian her associate in dishonest gain, she transferred to herself the whole wealth of the accused person."[20] The Secret History contains the information that sexual offenses were handled by the magistrate who held the office of "Quaesitor", a new office created as part of Justinian's administrative reforms. "Just as if the offices which had long been established did not suffice him for this purpose, he invented two additional magistracies to have charge of the State, although before that time the Prefect of the City was wont to deal with all the complaints. But to the end that the sycophants [public informers] might be ever more numerous and that he might maltreat much more expeditiously the persons of citizens who had done no wrong, he decided to institute these new offices. And to one of the two he gave jurisdiction over thieves, as he pretended, giving it the name of "Praetor of the Plebs"; and to the other office he assigned the province of punishing those who were habitually practising sodomy and those who had such intercourse with women as was prohibited by law, and any who did not worship the Deity in the orthodox way, giving the name of "Quaesitor" to this magistrate. Now the Praetor, if he found among the peculations any of great worth, would deliver these monies to the Emperor, saying that the owners of it were nowhere to be found. Thus the Emperor was always able to get a share of the most valuable plunder. And the one who was called Quaesitor, when he got under his power those who had fallen foul of him, would deliver to the Emperor whatever he wished to give up, while he himself would become rich nonetheless, in defiance of all law, on the property of other men. For the subordinates of these officials would neither bring forward accusers nor submit witnesses of what had been done, but throughout this whole period the unfortunates who fell in their way continued, without having been accused or convicted, and with the greatest secrecy, to be murdered as well as robbed of their money."[21]

According to John Malalas, Theodora took personal action against pimps and brothel-keepers who held poor girls under contract as early as 528. She would pay up to five solidi for each girl to free them from any obligation to their former employers. The price was set to the amount the brothel-keepers claimed they had paid to acquire the girls. The girls were to be provided with a solidus and a set of clothes for each of them. They were then supposedly dismissed to their own devices. Garland notes that under Justinian and Theodora brothels were outlawed. As of 535, brothel-keepers would no longer be able to receive any money for losing control of their girls. Laws of the year dictated that they would be punished by corporal punishment and exile.[22] Justinian and Theodora eventually created a convent on the Asian side of the Dardanelles called the Metanoia (Repentance), where the ex-prostitutes could support themselves.The main account on the subject is given in the "Buildings of Justinian" by Procopius. "There was a throng of women in Byzantium who had carried on in brothels a business of lechery, not of their own free will, but under force of lust. For it was maintained by brothel-keepers, and inmates of such houses were obliged at any and all times to practise lewdness, and pairing off at a moment's notice with strange men as they chanced to come along, they submitted to their embraces. For there had been a numerous body of procurers in the city from ancient times, conducting their traffic in licentiousness in brothels and selling others' youth in the public market-place and forcing virtuous persons into slavery. But the Emperor Justinian and the Empress Theodora, who always shared a common piety in all that they did, devised the following plan. They cleansed the state of the pollution of the brothels, banishing the very name of brothel-keepers, and they set free from a licentiousness fit only for slaves the women who were struggling with extreme poverty, providing them with independent maintenance, and setting virtue free. This they accomplished as follows. Near that shore of the strait which is on the right as one sails toward the Sea called Euxine, they made what had formerly been a palace into an imposing convent designed to serve as a refuge for women who repented of their past lives, so that there through the occupation which their minds would have with the worship of God and with religion they might be able to cleanse away the sins of their lives in the brothel. Therefore they call this domicile of such women "Repentance," in keeping with its purpose. And these Sovereigns have endowed this convent with an ample income of money, and have added many buildings most remarkable for their beauty and costliness, to serve as a consolation for the women, so that they should never be compelled to depart from the practice of virtue in any manner whatsoever. So much, then, for this."[23] Procopius also gives a less flowery description of the convent in his Secret History. According to it the prostitutes were sent there against their consent. He ignores Justinian and places blame for creation of the convent exclusively on Theodora. "But Theodora also concerned herself to devise punishments for sins against the body. Harlots, for instance, to the number of more than five hundred who plied their trade in the midst of the market-place at the rate of three obols — just enough to live on — she gathered together, and sending them over to the opposite mainland she confined them in the Convent of Repentance, as it is called, trying there to compel them to adopt a new manner of life. And some of them threw themselves down from a height at night and thus escaped the unwelcome transformation."[24]

John of Nikiû would later compare Theodora to some of the greatest reformers in Roman history for her campaign against prostitution. "There was a man named Romulus who had founded the great city of Rome; and likewise another who came after him named Numa, who adorned the city of Rome with institutions and laws, and subsequently established three orders in the empire. And so also subsequently did the great Caesar and Augustus also after him. And it was through these that the virtues of the Romans were shown forth, and these institutions are maintained among them until this day, And subsequently came the empress Theodora, the consort of the emperor Justinian, who put an end to the prostitution of women, and gave orders for their expulsion from every place."[25]

Religious policy

Theodora worked against her husband's support of Chalcedonian (Orthodox) Christianity in the ongoing struggle for the predominance of each faction.[11] In spite of Justinian being Orthodox Christian, Theodora founded a Monophysite monastery in Sykae and provided shelter in the palace for Severus, Anthimus, and other Monophysite leaders who faced opposition from the majority Orthodox Christians. Anthimus had been appointed Patriarch of Constantinople under her influence, and after the excommunication order he was hidden in Theodora's quarters for twelve years, until her death. When the Chalcedonian Patriarch Ephraim provoked a violent revolt in Antioch, eight Monophysite bishops were invited to Constantinople and Theodora welcomed them and housed them in the Hormisdas Palace, which had been Justinian and Theodora's own dwelling before they became emperor and empress.

In Egypt, when Timothy III died, Theodora enlisted the help of Dioscoros the Augustal Prefect and Aristomachos the duke of Egypt, to facilitate the enthronement of a disciple of Severus, Theodosius, thereby outmaneuvering her husband who had been plotting for a Catholic successor as patriarch. But Pope Theodosius I of Alexandria, even with the help of imperial troops, could not hold his ground in Alexandria against the Julianists and when he was exiled by Justinian along with 300 Monophysites to the fortress of Delcus in Thrace, Theodora rescued him and brought him to the Hormisdas Palace where he lived under her protection, and after her death in 548, under Justinian's.

Garland notes that Theodora seems to have to held respect for members of the Chalcedonian faction as well.She mentions as evidence the life of Sabbas the Sanctified, written by Cyril of Scythopolis. According to this biographical account, the elderly monk visited the court at Constantinople in 531. The imperial couple received him with prostration before him, "a gesture of veneration for desert ascetic saints". Theodora reportedly took the opportunity to ask him to remember her in his prayers, specifically asking God to allow her to conceive a child. However, her monophysitic leanings were already familiar to him. He refused her request and proclaimed that "no issue will come from her womb". Abbas reportedly explained that a child of Theodora would probably adopt the doctrines of Severus and cause more trouble to the church than Anastasius I had. Keeping in mind Anastasius was the last monophysite emperor, this would mean that in Sabbas' eyes Theodora was an enemy and Justinian not fervent enough in his support of the Chalcedonians. The text notes the great grief of Theodora at such a harsh rejection of her request.[26]

When Pope Silverius refused Theodora's demand that he remove the anathema of Pope Agapetus I from Anthimus, she sent Belisarius instructions to find a pretext to remove Silverius. When this was accomplished, Vigilius was appointed in his stead.

Conclusively, Theodora's policy on theological matters was separatist. One could argue, as the Chalcedonians did, that Theodora fostered heresy and thus undermined the unity of Christendom. But it would be equally fair to say that Theodora's policy delayed the alienation of the eastern church, and might have postponed it indefinitely but for external events she could not control or foresee.

Another incident, which shows how far Theodora could go to thwart her husband on religious matters, is the case of Nobatae, south of Egypt, whose inhabitants were converted to Monophysite Christianity about 540. Justinian had been determined that they be converted to the Chalcedonian faith and Theodora equally determined that they should be Monophysites. Justinian made arrangements for Chalcedonian missionaries from Thebaid to go with presents to Silko, the king of the Nobatae. But on hearing this, Theodora prepared her own missionaries and wrote to the duke of Thebaid that he should delay her husband's embassy so that the Monophysite missionaries should arrive first; otherwise he would pay for it with his life. The duke was canny enough to thwart the easygoing Justinian instead of the unforgiving Theodora. He saw to it that the Chalcedonian missionaries were delayed. When they eventually reached Silko, they were sent away, for the Nobatae had already adopted the Monophysite creed of Theodosius.

Death

Theodora died of an unspecified cancer on 28 June 548 before the age of 50, 17 years before Justinian. Her body was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles, in Constantinople. Though it has been argued that the sole source for her illness, Victor of Tonnena, may not use the word "cancer" in its modern medical sense, yet cancer seems to be the best guess. (There is no documentation to suggest that she died of breast cancer, as some scholars have suggested.) Justinian wept bitterly at her funeral.[27]

Both Theodora and Justinian are represented in mosaics that exist to this day in the Basilica of San Vitale of Ravenna, Italy, which was completed a year before her death. Garland points that Theodora was depicted in full imperial regalia, her elaborate jewellery attesting to her status. Her chlamys depicts the Biblical Magi bringing their gifts to newborn Jesus. Garland considers the imagery was chosen specifically to emphasize the role of a Theodora as a donator to the Basilica. The Communion chalice which Theodora holds on her hand represents her gifts.[12]

Garland points that Theodora was also depicted with Justinian in a work of art described in detail by Procopius. The specific reference is to the ceiling mosaic of the Chalke gate.[12] "On either side is war and battle, and many cities are being captured, some in Italy, some in Libya; and the Emperor Justinian is winning victories through his General Belisarius, and the General is returning to the Emperor, with his whole army intact, and he gives him spoils, both kings and kingdoms and all things that are most prized among men. In the centre stand the Emperor and the Empress Theodora, both seeming to rejoice and to celebrate victories over both the King of the Vandals and the King of the Goths, who approach them as prisoners of war to be led into bondage. Around them stands the Roman Senate, all in festal mood."[28] Garland regards that the depiction of Theodora receiving imperial honours on both occasions has a political significance. It was ensuring that her regal status was not seen as inferior to that of Justinian by their subjects.[12]

Known family members

John Malalas records that Comito, her older sister, married General Sittas in 528.[29] Sittas may thus be the father of Sophia, Theodora's niece.[30] Whether Anastasia, her younger sister, ever married is unknown.[31] Theophanes the Confessor names Georgius (George) and Ioannes (John) as relatives of Theodora.[3]

Procopius mentions a marital alliance between Theodora and General Belisarius, specifically of Anastasius, her grandson, and Joannina, his only daughter.[32] He and other sources (Bar-Hebraeus, Michael the Syrian) also mention "Athanasius, son of the Empress Theodora's daughter."[33] The daughter of Theodora is almost never named in sources despite the mentions of at least three of her sons.[3] The daughter was probably illegitimate and the identity of her father remains uncertain.[34] Justinian apparently treated the daughter and the daughter's son Athanasius as fully legitimate,[35] although sources disagree whether Justinian was the girl's father. Garland simply points that our sources mention Theodora's daughter and Theodora's grandsons. No source speaks of Justinian's daughter or Justinian's grandsons.

On the subject of Theodora's grandsons, Garland notes that they were "prominent members of the court and the establishment."[26] John held the rank of consul. Athanasius was a monk and a leading figure among the Monophysites. He seems to have administrated considerable wealth. As stated already, Anastasius married Belisarius' daughter.[36]

Procopius also mentions John, an illegitimate son of Theodora. He claims she had John exiled or killed to hide his existence from Justinian.[37] Theodora had openly recognized an illegitimate daughter and at least three grandsons, so modern historians question why would the existence of an illegitimate son would be considered a greater scandal, sufficient to be kept secret and the son to be "done away with". James Allan and Stewart Evans suggest that John was merely an impostor attempting to enter the ranks of the imperial family.[38]

In recent times, it has come to light that the daughter's name was also Theodora, that she was born circa 515 and that she was married by her mother to Flavius Anastasius Paulus Probus Sabinianus Pompeius (ca 500 - aft. 517), Roman Consul in 517.[39]

Lasting Influence

Her influence on Justinian was so strong that after her death, he worked to bring harmony between the Monophysites and the Orthodox Christians in the Empire, and he kept his promise to protect her little community of Monophysite refugees in the Hormisdas Palace. Theodora provided much political support for the ministry of Jacob Baradaeus, and apparently personal friendship as well. Diehl attributes the modern existence of Jacobite Christianity equally to Baradaeus and to Theodora.[40]

Theodora is considered a great female figure of the Byzantine Empire, and a pioneer of feminism, because of the laws she passed, increasing the rights of women. As a result of Theodora's efforts, the status of women in the Byzantine Empire was elevated far above that of women in the Middle East and the rest of Europe.

City naming

It was normal that ancient cities took other names to honor an emperor or empress. Olbia in Cyrenaica renamed itself Theodorias after Theodora. The city, now called Qasr Libya, is known for its splendid sixth-century mosaics.

References

- ↑ Commemorated on November 14. Retrieved on 12 November 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 James Allan Evans, "Theodora (Wife of Justinian I)"

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, vol. 3

- ↑ From Rome to Byzantium: The Fifth Century A.D., Michael Grant, Published by Routledge, p.132. Does the Future Hold for Mankind, R. A. Bowland, Xlibris Corporation, p.77. A Complete History of the Lives, Acts, and Martyrdoms of the Holy Apostles, William Cave, Published 1810 Solomon Wiatt, p.131. The Genuine Epistles of the Apostolic Fathers, Clement, Polycarp, Ignatius, Hermas, William Wake, William Adams, William Cave, 1834 Parsons and Hills, p. 214. Europe: A History, Norman Davies, 1996 Oxford University Press, p.242. The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire 2 Volume Set., J. R. Martindale, 1992 Cambridge University Press, p.1240. A dictionary of Christian biography, literature, sects and doctrines; being a continuation of 'The dictionary of the Bible', Henry Wace, William Smith, 1882 J. Murray, Stanford University, p.539

- ↑ Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", page 13

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Procopius of Caesarea, The Secret History, chapter 9. 1927 translation by Richard Atwater.

- ↑ Procopius of Caesarea, The Secret History, chapter 9. 1927 translation by Richard Atwater.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Procopius of Caesarea, The Secret History, chapter 10. 1927 translation by Richard Atwater.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Annotated Justinian Code. Book 5, title 4, chapter 23. 1943 translation by Fred H. Blume

- ↑ Lynn Hunt et al., The Making of the West: Peoples and Cultures, Boston Bedford, 2001, p. 263.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Theodora - Byzantine Empress". About.com. http://womenshistory.about.com/library/bio/blbio_theodora.htm. Retrieved 2008-04-11.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", page 21

- ↑ Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", page 18

- ↑ Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", page 20

- ↑ Procopius, Buildings. Book 1, Chapter 2 1940 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ Procopius, Buildings. Book 5, Chapter 3 1940 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ Procopius, Buildings. Book 6, Chapter 5. 1940 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", pages 16-17

- ↑ Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", page 16

- ↑ Evagrius Scholasticus, Ecclesiastical History, Book 4, chapter 30. 1846 translation by Edward Walford.

- ↑ Procopius, Secret History. Chapter 20. 1935 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", pages 17-18

- ↑ Procopius, Buildings. Book 1, Chapter 9 1940 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ Procopius, Secret History. Chapter 17. 1935 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ John of Nikiû, Chronicle, Chapter 93. 1916 translation by Robert Henry Charles

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Lynda Garland, "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204", page 23

- ↑ Diehl, ibid., p.197.

- ↑ Procopius, Buildings. Book 1, Chapter 10. 1940 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ PLRE, vol. 3, Sittas

- ↑ J. B. Bury, History of the Later Roman Empire from the Death of Theodosius I to the Death of Justinian (1923)

- ↑ Lynda Garland, "Sophia, Wife of Justin II"

- ↑ The Secret History of Procopius, Chapter 4. 1935 translation by H. B. Dewing

- ↑ The Secret History of Procopius, Chapter 4. Introduction by H. B. Dewing

- ↑ Profile of Justin I and his family in "Medieval Lands" by Charles Cawley

- ↑ Diehl, Charles. Theodora, Empress of Byzantium ((c) 1972 by Frederick Ungar Publishing, Inc., transl. by S.R. Rosenbaum from the original French Theodora, Imperatice de Byzance), 69-70.

- ↑ Procopius, Secret History. Chapter 5. 1935 translation by H. B. Dewing.

- ↑ Procopius of Caesarea, The Secret History, chapter 17. 1927 translation by Richard Atwater.

- ↑ James Allan and Stewart Evans, "Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power" (1996), page 102

- ↑ Continuité des élites à Byzance durante les siècles obscurs. Les princes caucasiens et l'Empire du VIe au IXe siècle, 2006

- ↑ Diehl, ibid., p.184.

Further reading

- Diehl, Charles. "Theodora, Empress of Byzantium" ((c) 1972 by Frederick Ungar Publishing, Inc., transl. by S.R. Rosenbaum from the original French "Theodora, Imperatice de Byzance"). Popular account based on the author's extensive scholarly research.

- Gibbon, Edward. "The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire". (See volume 4, chapter 40 for Gibbon's account of Theodora.)

- Graves, Robert. "Count Belisarius". (A historical novel by the author of "I, Claudius" which features Theodora as a character.)

- Bury, J. B. "The Later Roman Empire". (Volume 2 deals with the reign of Justinian and Theodora)

- Procopius The Secret History at the Internet Medieval Sourcebook

- Procopius The Secret History at LacusCurtius

External links

- De Imperatoribus Romanis - Theodora (Wife of Justinian I)

- Gibbons' The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire: The Fall of the Roman Empire in the East

- Then again - The Empress Theodora

- Litopia - Empress Theodora

- Her profile in the Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire

- Profile of her older sister Comito in the Prosopography

- Her chapter in "Byzantine Empresses: Women and Power in Byzantium, AD 527-1204" by Lynda Garland

- Page of "Procopius and the Sixth Century" by Averil Cameron which gives details about her descendants

- Page of "The Age of Justinian" discussing her son John

- Page of "A History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene" which details her involvement in the affairs of Praejecta

| Royal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Euphemia |

Byzantine Empress 527–548 |

Succeeded by Sophia |